From Amsterdam to Portugal: Dutch innovation turns bubbles into clean rivers

Every minute, more than a truckload of plastic enters the ocean. Most of it is carried by rivers. In 2017, a group of Dutch and German innovators set out to intercept plastic upstream with The Great Bubble Barrier. This year, the initiative marked two major milestones: more than one million pieces of plastic captured in Amsterdam’s canals, and finalising the successful implementation of its first international pilot project in Portugal.

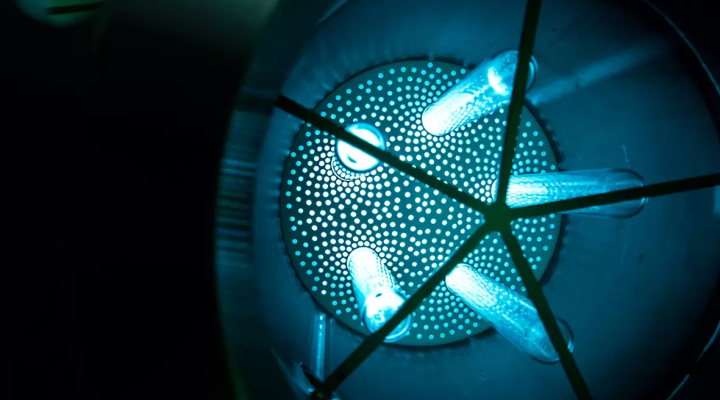

Turning bubbles into barriers

The concept is as simple as it is ingenious. A perforated tube, laid diagonally across a riverbed, pumps a steady stream of air to create a curtain of bubbles. This invisible wall guides plastic waste to the surface and towards a catchment system at the riverbank. Meanwhile, fish and boats are able to pass freely. Beyond intercepting waste, it also gently aerates the water. This improves oxygen levels and supports aquatic life.

From an idea to an impact-driven enterprise

The story of The Great Bubble Barrier started in 2017. Back then, three Dutch women – Anne Marieke Eveleens, Francis Zoet, and Saskia Studer – teamed up with German environmental engineer Philip Ehrhorn. Independently, they had been working on a similar idea: bubbles that could move debris in water.

Two years later, the first long-term Bubble Barrier was installed in Amsterdam’s Westerdok. It was commissioned by the City of Amsterdam and Waterschap Amstel, Gooi en Vecht, becoming the first system of its kind worldwide.

One million pieces – and counting

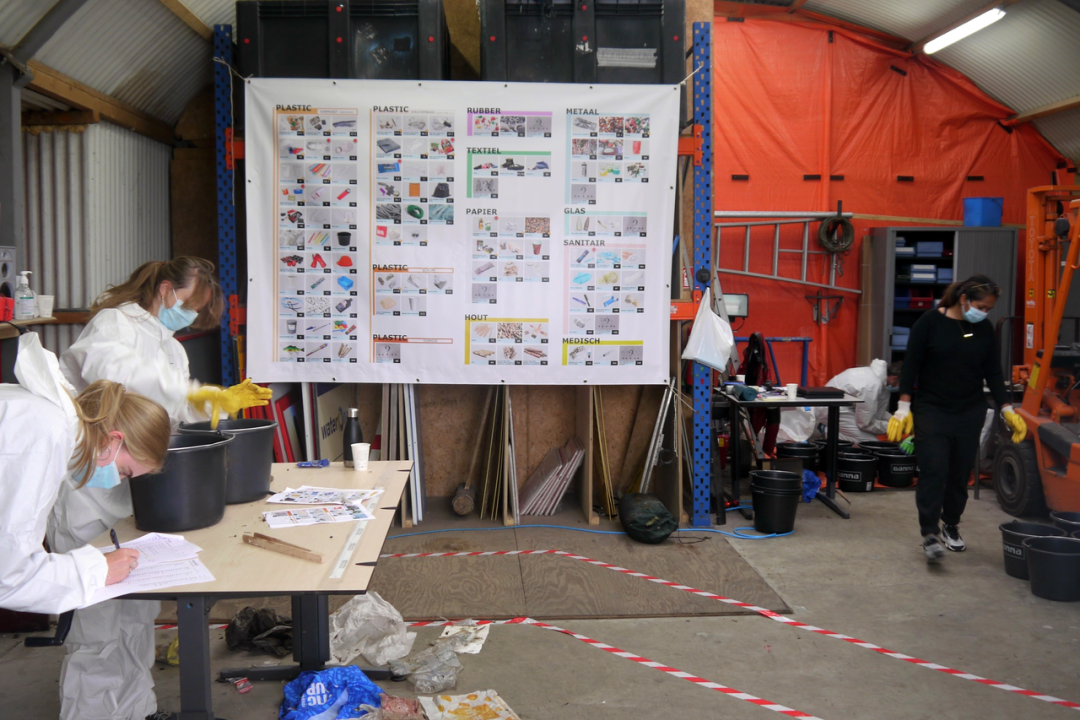

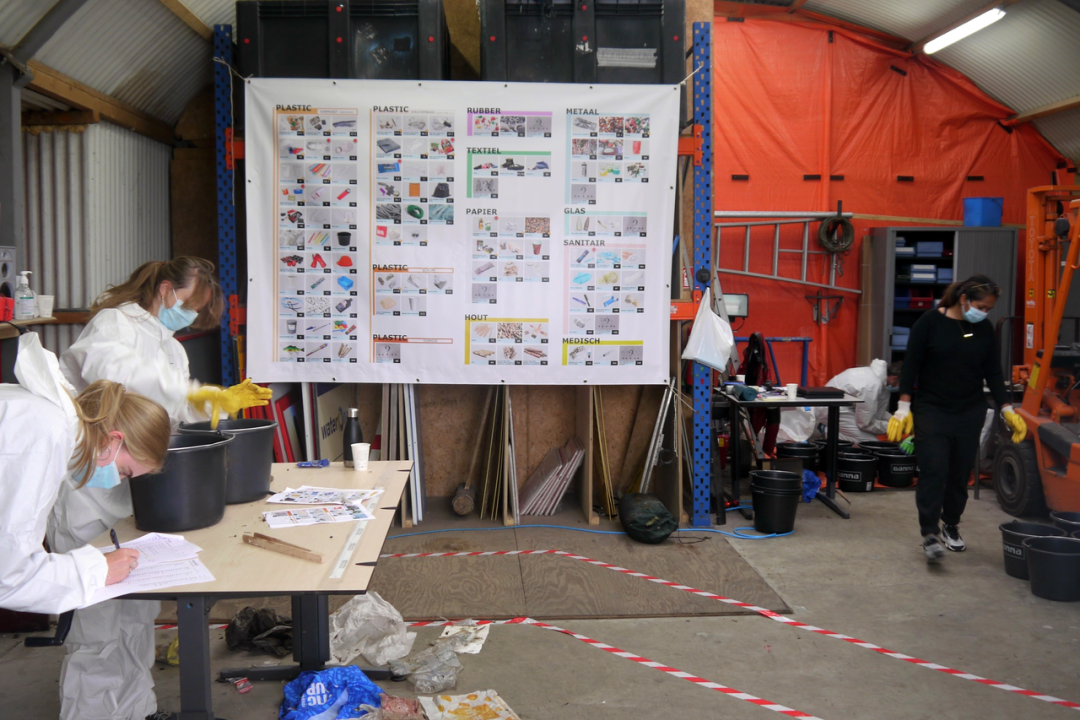

Since its launch in 2019, Bubble Barrier Amsterdam has intercepted over one million pieces of plastic. To monitor its impact, every item collected over the course of a year was counted, analysed, and categorised in collaboration with partners including Waternet and the Plastic Soup Foundation. On average, the barrier captures around 15,000 pieces – roughly 80 kilograms – of waste every month.

To celebrate the milestone, local councillors and policymakers gathered at the “Museum of Plastic” during SAIL Amsterdam 2025. This installation displayed some of the most unusual findings. The event was both a celebration and a call to action – urging cities to invest in innovative, collaborative solutions to stop plastic pollution at its source.

“Reaching one million pieces caught is more than a number – it’s a statement that innovative, collaborative solutions work,” shares Anne Marieke Eveleens, Co-founder of The Great Bubble Barrier, on the enterprise’s LinkedIn page. “It’s a milestone we share with every partner and citizen committed to keeping Amsterdam’s waters clean.”

Collaboration as the driving force

A key factor behind the success of the Bubble Barrier is close collaboration between the public and private sectors. In Amsterdam, the system was implemented in partnership with Waterschap Amstel, Gooi en Vecht and the Municipality of Amsterdam as part of the city’s ambition to achieve plastic-free waterways by 2030.

The Bubble Barrier Amsterdam complements daily clean-up efforts led by drinking water company Waternet and captures plastic that would otherwise remain below the surface. Operating around the clock and powered by renewable energy, the installation removes waste across the full width and depth of the city’s designated canal.

Similar collaborations underpin other Bubble Barrier projects across the Netherlands. Municipalities, provinces, water boards, knowledge institutes, drinking water companies, and technical partners all play a vital role in developing and scaling these systems. Working closely with these actors ensures that innovative solutions like the Bubble Barrier can be seamlessly integrated into local urban and water management.

From Amsterdam to Portugal: the first estuarine Bubble Barrier

In 2023, The Great Bubble Barrier took an important step abroad. It piloted its first international Bubble Barrier in Vila do Conde, Portugal, under the EU-funded MAELSTROM project. The barrier was installed in the Ave River. More specifically, in the river’s estuarine zone, where salt and freshwater meet.

The design marks the first Bubble Barrier ever placed in an estuary. The system was specially adapted to handle tidal reversals and shifting flow patterns – challenges typical of estuarine environments.

In 2025, the MAELSTROM consortium received the Blue Rivers & Lakes Award for Innovation at the European Ocean Days. The pilot showed promising results, capturing an estimated 2,700 plastic items – around 17 kilograms – each month. As a result, the Municipality of Vila do Conde intends to continue operating the Bubble Barrier’s operation. Together, these achievements set a valuable precedent for future estuarine projects across Europe.

Recognition and awards

Innovation rarely goes unnoticed. Recently, The Great Bubble Barrier was announced as a finalist for the 2026 Zayed Sustainability Prize in the Water category – one of only 33 finalists chosen from more than 7,700 submissions worldwide. In addition, the social enterprise has been nominated for the KvK Innovatie Top 100 by the Dutch Chamber of Commerce.

Challenges on the way to scale

Although successful, the path to expansion is not without obstacles. Policy gaps remain one of the main challenges. Many governments have mandates to remove waste from streets but not from rivers once it enters the water system. As a result, funding for river-based clean-up measures is often scarce. Finding long-term, impact-oriented investors has also been a challenge.

Scaling impact through cooperation

Despite its challenges, The Great Bubble Barrier continues to grow organically through partnerships and public contracts. The company is already preparing to work with other European cities and river authorities to deploy new barriers. The success of this innovative water technology demonstrates that simple, public–private and collaborative solutions can have a powerful impact on cleaner waterways worldwide.