WWWeek at home: No sediment flow, no river delta

Low lying river deltas are more under threat from the decrease of sediment flow rather than from sea level rise. This was the central message of the session titled 'Sinking, shrinking, saltier deltas'.

The session was part of the Stockholm World Water week 2020 home edition and was organised by the research institute Deltares and the knowledge network Delta Alliance and World Wide Fund for Nature.

Natural balancing act

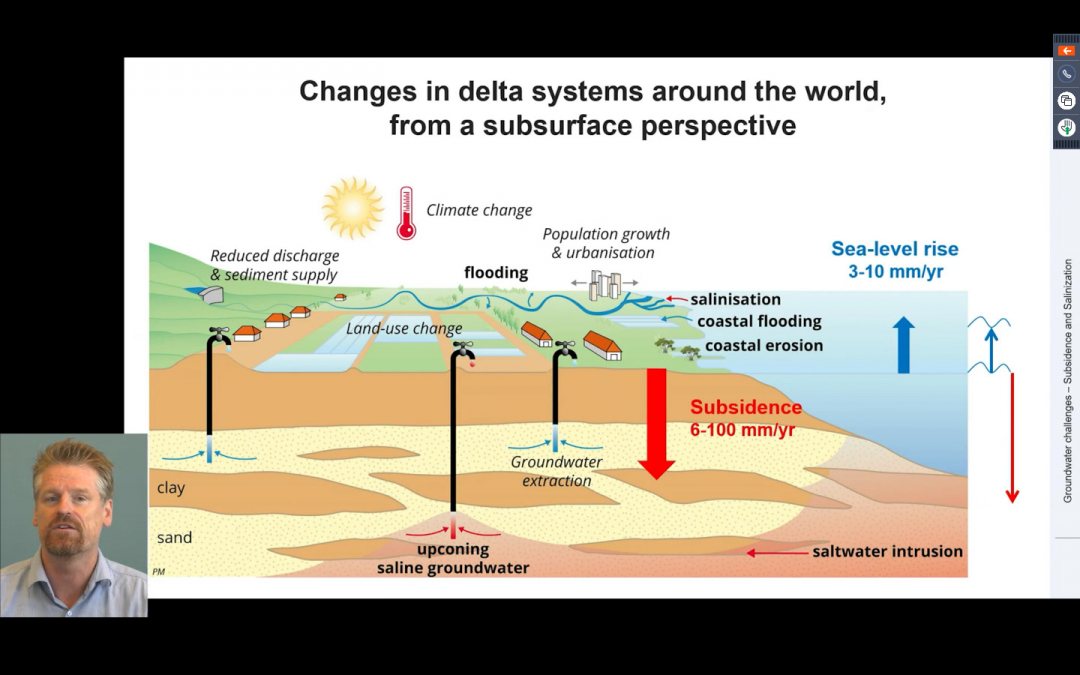

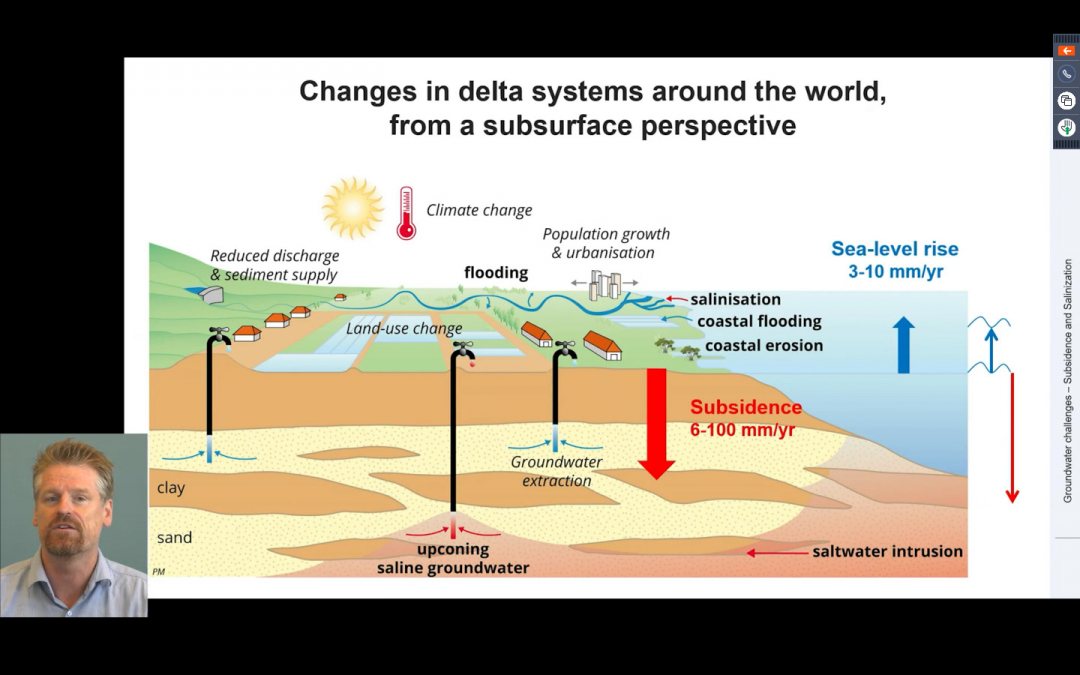

The sediment that deltas receive from the upstream river is what makes them grow. Subsidence is a delta's natural ‘enemy’ and when the transport of sediment stops the delta loses the ‘fight’ and will eventually sink. The awareness for climate change and future sea level rise makes it widely understood that coastal areas are at risk. This awareness, however, is only one part of the story. During the session, senior expert Gualbert Oude Essink at Deltares remarked that land subsidence is a far bigger threat than sea level rise.

Subsidence in river deltas varies from 6 to 100 mm per year. ‘This is much more substantial than the annual sea level rise of 3 to 10 mm’, said Oude Essink. ‘So what happens inside the delta is more important than outside.’

During the session several human activities were highlighted such as the decreasing sediment flows because of dams and sand mining.

Complex processes

Marc Goichot of World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) told that many rivers in the world are facing a quick decreasing sediment flow, leaving the downstream delta with only little deposition.

Goichot explained the complex morphological processes in a river delta and the far reaching effects of the sediment reduction. He took the Mekong delta in Vietnam as an example. ‘It is a good example for any large tropical river delta with changing weather patterns that make the wet season more wet and the dry periods more dry. This causes higher peak flows in the river, causing more floods and erosion’, he said.

Sand traps and mining

Based on several recent studies it is estimated that the sediment transport in the Mekong river has dropped from 160 million ton, before the first dams were built in China, to 5 million ton now. According to Goichot much of the sediment is trapped in the reservoirs of the hydro dams. But he also pointed out the huge volumes of sand mining that takes place all along the river. Recent studies indicate the 80 – 100 million ton is removed from the river to end up in construction projects.

Goichot urges authorities to make sediment estimates more often in order to be able to analyse the sediment inputs (sources) and outputs (sinks). This can be used to predict morphological changes over time.

The sediment flow is a growing issue as many plans to increase the production of renewable energy include the construction of hydrodams. This is especially the case with rivers in Africa.

Illegal sand miners arrested

Environmental Economist Le Thu Thi Nguyen at the World Bank spoke some hopeful words. The recent studies on the sediment flows in the Mekong river has contributed to a rethinking on how to handle the issues of new dams. ‘The government has introduced a new law that makes it possible to arrest people for illegal sand mining. Groundwater extraction limitations have been introduced for specific zones. And local governments have a better understanding of these specific delta issues.’ Le Thu hopes that all this will lead to improvement in the next 10 to 15 years.

See the full programme on the website of World Water Week. The sessions are organised by different institutions and all use different procedures, so be sure to check beforehand if you need to register to join a session.