Toxic algal bloom fuelled by higher CO2-levels in water

At high CO2-concentrations, cyanobacteria can absorb a factor five more CO2 in comparison to other types of algae that live in water. This can intensify cyanobacterial growth and increases the amount of toxins in surface waters.

This finding has recently been published in an article of the journal Science Advances by scientists from the University of Amsterdam, Netherlands Institute of Ecology, East China Normal University of Shanghai and the University of Bremen.

High CO2-levels in water

The scientists tested the culture of the most common toxic cyanobacteria, Microcystis, at low and high CO2 concentrations. According to the scientists lab tests showed an increase of the CO2-uptake by a factor 5. This gives the toxic bacteria a growth advantage.

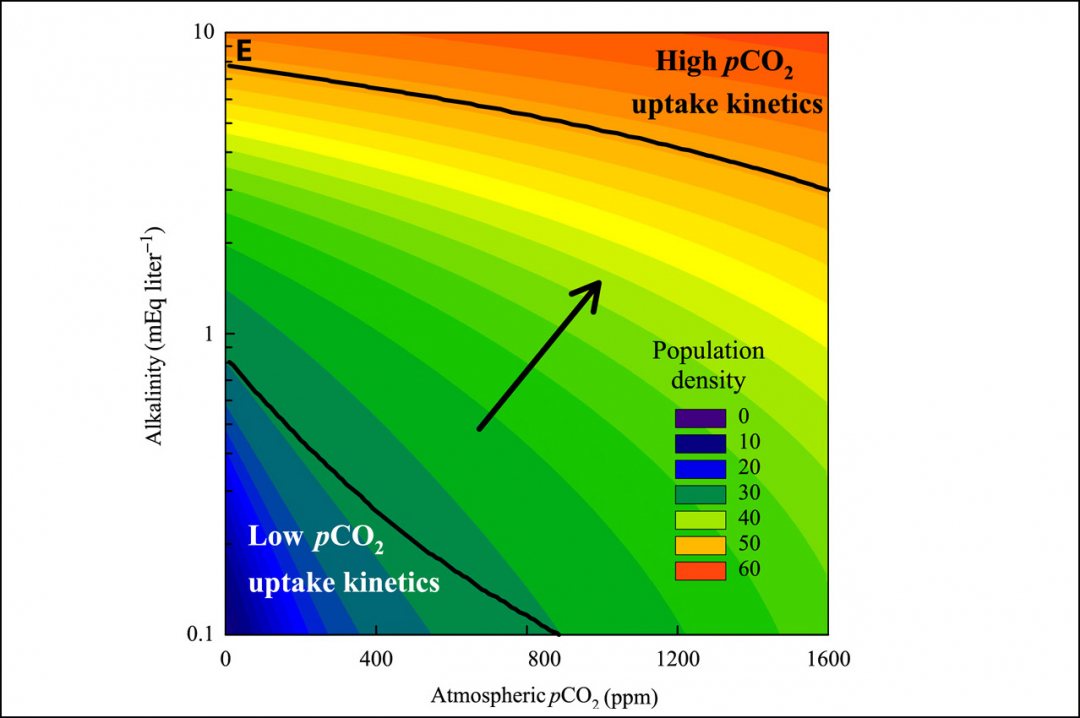

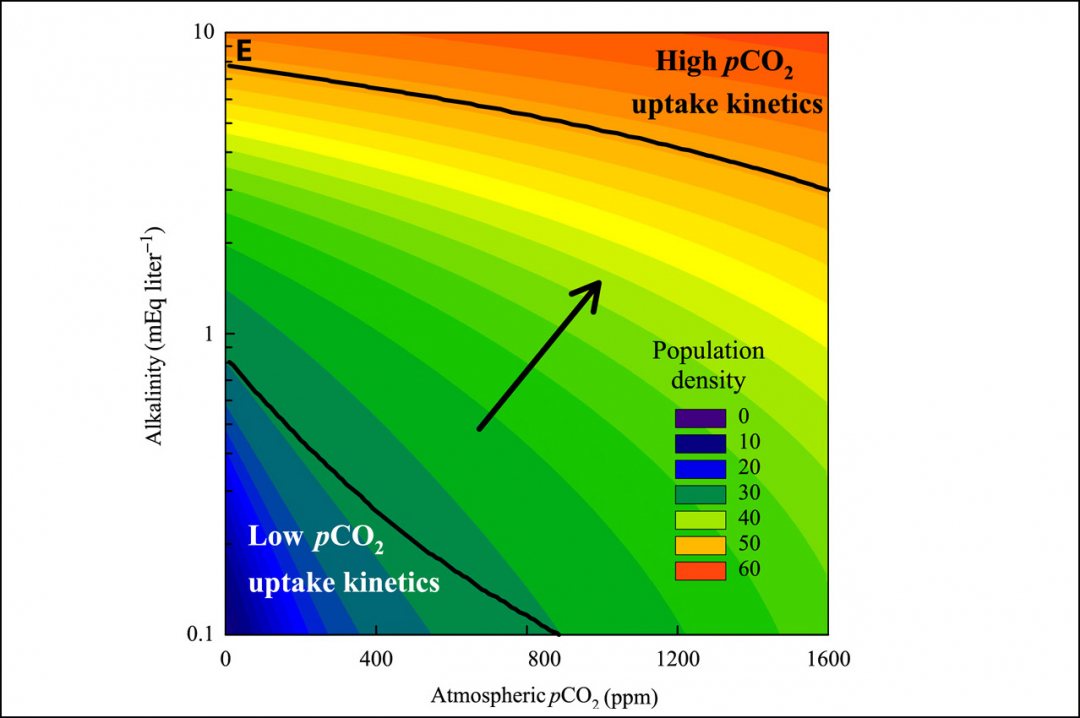

The observed plasticity was incorporated into a model to predict changes in cyanobacterial abundance.

More CO2 in atmosphere

The rising of CO2 in surface water is a topic, as rising concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere, will automatically lead to more CO2 in surface waters.

"The study shows that cyanobacteria increase their photosynthesis when there is more CO2", says NIOO-researcher Dedmer van de Waal. "This could give them an advantage in the future if CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere continue to be high."

Fertilising water

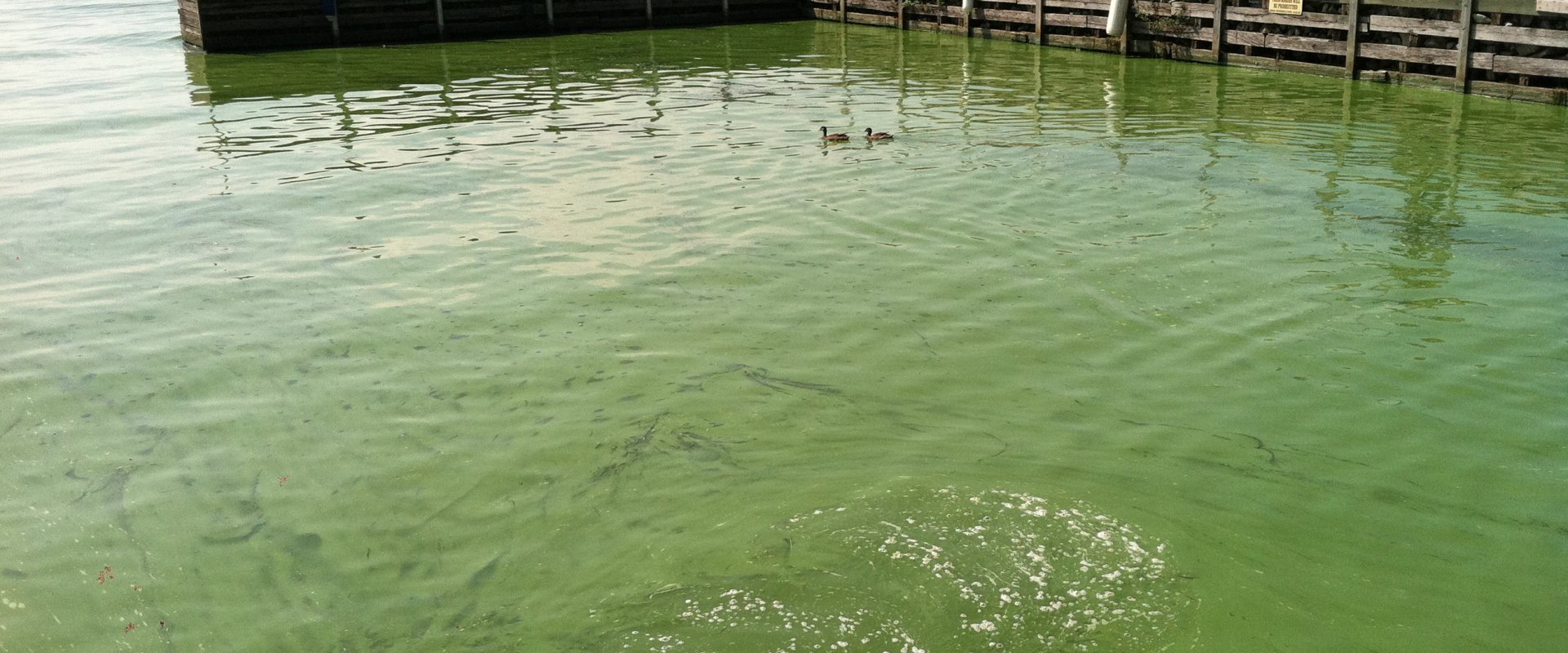

Each summer, the water quality of lakes and ponds is threatened by the growth of cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae. Cyanobacteria can produce a variety of toxins that are harmful to humans, other mammals and birds. In humans, these toxins may cause nausea, dizziness and even liver damage.

Intense cyanobacterial growth increases the amount of toxins in the water, which can negatively affect the use of lakes for recreation, drinking water or fisheries.

Cyanobacterial growth already affects water quality across the globe, for example in Lake Erie (USA). ‘We're basically fertilising waters with CO2 on a global scale’, says researcher Jolanda Verspagen of the University of Amsterdam.

The full article can be read on Science Advances.